What Transcends From Rot

Can the Earth forgive?

You’re reading the second story in Bodies, Tractor Beam’s Halloween mini-issue, a collection of three short stories on death and decomposition. You can read the first story here. Subscribe to receive future mini-issue editions as they drop exclusively here on Substack!

Story by: Ciarra Havon

Annotations by: Sophie Strand

Art by: Samir Sirk Morató, Deborah D. Gabriel-Whyte, P I Megha Vinod, Ona Vidūnaitė, Finn Jones, Kai Feldhammer, Mirabelle Korn

My eulogy starts as all such gatherings start now.

“My community.”

“Your community.”

“Today we gather to accept the death of one of our own, Caiden Haughman. Caiden is survived by his daughter Rebecka, his two sons Blake and Ryder in the stars, his child Phoenix, and his hero Tahani. He was preceded in death by his wife Madisynn, mother Scarlet, grandmother Josie, and grandfather Clint.

We here knew Caiden as the man to call when we were in need. He learned to sew and knit to make clothes for Daisy’s premature twins. He lived in his shed for two months when the Gunderson family’s house burned down so they could stay in his house while also using his woodworking skills to help rebuild. He might not have been who you went to for a good cry, but he could make you laugh about it instead.

But these are not the only stories Caiden wanted me to leave with you. He was also a man of faults who later in life walked the path of repentance.

Caiden grew up in an age that cared for The Great Mother as it cared for humanity–not at all. He and his fathers demanded more and more from the earth, their children, the women they purportedly loved. As Caiden grew older, he enacted those same sins on his family. Even after his wife died of a cancer that spread too fast with the health care she desperately needed behind a paywall, he remained loyal to the powers that killed her. In his darkest hour, he damned his own child to a life on the streets when xey revealed xer truest self.

His life could have languished in isolation, disparity, and pain, but the great Huntsville floodwaters that killed hundreds woke him. It was this baptismal font that opened Caiden’s eyes to see that the people in power, those that he trusted more than his family, didn’t care. There was no help coming except for the community around him. In this hour, he listened. He pulled men, women, and children out of the floodwaters, saving himself as well as them. He sold his home in the time of land ownership to help pay for the victims to rebuild their lives. He housed teenagers who, like his child Phoenix, were rejected by their families for the supposed crime of being born different. He repaired his relationship with his daughter Rebecka and attempted to change the hearts of his sons before they made the decision to leave the Earth. Caiden learned to listen and respect those around him. He asked for forgiveness, but only after trying to repair what he’d broken. Caiden’s life shows us there is potential for growth, atonement, and hope in all of us. His legacy is one of metamorphosis.

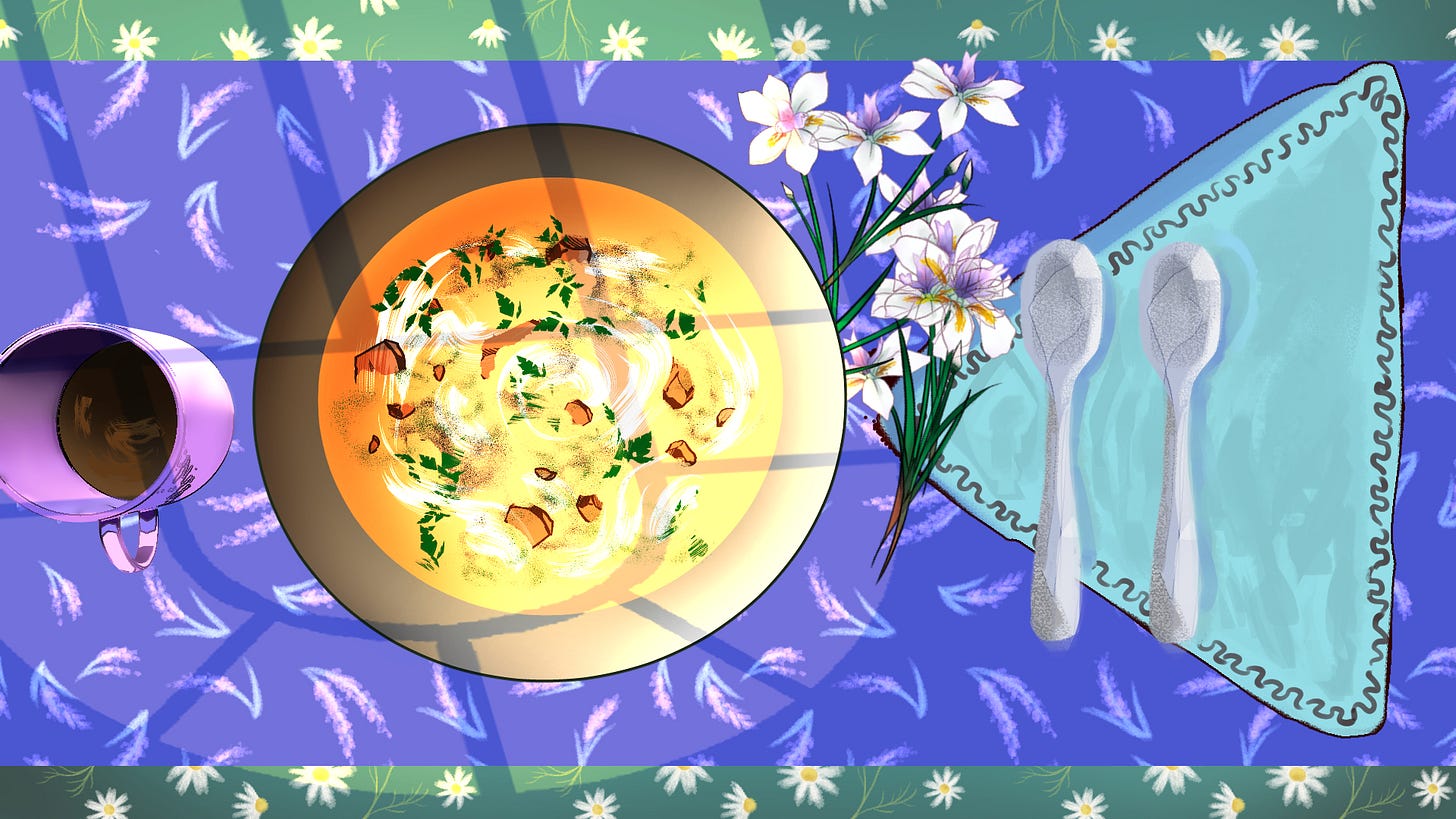

Even now, Caiden supports his home as he returns his sustenance to the soil in appreciation of the nourishment he has been given by The Great Mother Earth. He has chosen to grow winter squash with his body. Butternut squash soup was his mother’s favorite dish. Eating it always made him feel warm and secure. He passes down his mother’s recipe to his daughter Rebecka in hopes that in the coming seasons, he will be able to give her the same comfort. In life, he could not breach the hurt he caused his youngest child, Phoenix. In death he hopes to give xem peace and perhaps the same butternut squash soup should xey ever desire. The rest of his bounty will be given to the community to allocate as is needed.

He wishes us good work, good deeds, and good feelings. He is buried among the memories of those who loved him into being in the hope that his memories, experiences, and joy will assimilate into The Great Mother to heal her just as his carbon, nitrogen, and biomass will.

Walk in understanding and love.”

“We will,” comes the response. I believe them.

****

It’s a year earlier, a hazy morning, late June. I’m packing my bag for the day when a text comes in.

“Dad had a really good night last night :)”

Well, that settles it. Mr. Haughman is going to die today. They almost always have a good day right before they go. It can make it harder on the families, some take it as a sign of more time—but it’s good for the dying to say their goodbyes and leave the earth in less pain.

I take out some of the pain herb sachets I made and replace them with more of my calming herbs. Rebecka will likely need the help after. It can make it harder on the families, these good days; they take it as a sign of more time.

I double check that I have Mr. Haughman’s end-of-life journal and part of the soil he will be buried with. I smell the bag it’s in, breathe in its intoxicating scent. It’s spent the last several days soaking in the sun, the moon, the rain, and the dried lotuses I’ve crushed in. It smells slightly of sweet rot, and of potential; it smells of rebirth.

“It’s a beautiful ritual, yes, but it’s also introducing new bacteria, protozoa, actinomycetes, and microscopic amounts of fungi into his resting place.”

****

When I arrive at Rebecka’s house, things are cheerful. I don’t even have to knock.

“Duella!” she whoops as she throws open the door, “you have to see Dad, he’s like ten years younger!” She leads me through the familiar house as she continues, “I swear, you’re a miracle worker. He didn’t wake up a single time last night, didn’t need any pain medication, and this morning he’s just been, been,-” she’s trying to catch a word in the air, “-effervescent. But you’ll see!”

And there he is, sitting up in bed, his smile wide and no trace of the grimace of pain that’s been a fixture on his face for weeks.

“Duella! It’s good to see you. Sit with me for a spell.” His voice doesn’t waver and his breath is strong.

I smile. “It’s good to see you too. I’m glad you’re feeling so well. Let me get some things out of my bag and I’ll settle down with you.” I take out the journal and the small bag of soil while Mr. Haughman gives Rebecka a task that will keep her out of the room for a while. I take longer than I need to, riffling through all my things until she leaves. When she finally does, I turn and smile at Mr Haughman as I sit down and take his hand.

“I’m going to die today, aren’t I, Duella?”

I nod, “Yes, more than likely.”

“Good, good. It’s a blessing to die feeling more like myself.” He swallows, “Will it be terribly hard on her, when I go?”

“It will always be hard, Caiden. Some people think it’s easier when it’s expected, but the truth is that you can’t get used to something that hasn’t happened yet. The grief of others isn’t a thing you can control.”

I’ve said as much a hundred times in my time with Mr. Haughman, but this constant reassurance is so needed before transition. My friends had echoed similar refrains during and before my own transition into womanhood.

I pass Mr. Haughman the bag of soil. His hands don’t shake as he takes it from me. “Tell me the story of this soil you have chosen.”

He brings the bag up to his nose and inhales deeply. “Is it rude to say it smells a bit like my wife?”

This makes me laugh, “Believe or not, you’re not the first person to tell me that. I take it as a compliment; I worked real hard on making that soil healthy. Your wife must have been full of life.”

He nods, but looks away. I’ve been around him long enough to know this means he’s tearing up. Some habits die hard. “I miss her.” His voice cracks and I see a few tears land on his blankets. “She smelled like that when she was pregnant with our girls. Like it does after rain. I don’t know if I can describe it very well…” he trailed off, “I guess what I mean is that she smelled like growth.”

He holds the bag up to his nose and takes more drags of it into himself. “I miss her and I don’t think I’ll ever see her again. I used to be so sure, but what if we killed heaven?” The tears are falling in multitudes now.

I still never know quite what to say in these moments. I’ve been a Transition Doula for eight years now, but what can you say to truly comfort someone who sees death bearing down on them? I hate platitudes, promises that everything will be better or work out, because I don’t know if things will be better or work out. I’ve found that the most important thing I can do for my clients is to be here, to hold their hand as they evolve to their next state; from life to death, from married to divorced, from child to woman, from expectant to parent.

So grasp his hand in mine and rest my head on top of our intertwined fingers. I am here, I am with you.

His breathing slows, the tears dry, he inhales fresh air and turns to me again. He clears his throat, “This soil-,” He swallows. “This soil is from my grandparent’s house. They were the last in my family to work the land. My father sold it to a developer when they died. I miss the freedom there, the sense of being connected to something bigger than myself. This soil reminds me of my mother, my grandmother, my grandfather. I want to be surrounded by those memories as my body helps to heal the soil here.”

He takes a long, deep breath before looking me in the eyes. “Do you think it can be done? Do you think we can heal Her?”

These days, it’s the question on everyone’s minds, on the tips of all our tongues. I answer slowly, “I don’t know if we can heal Her. But I think we can start to atone for what we’ve done, and maybe the Earth will forgive us and heal Herself.”1

He nods, settles back into his pillows. “I have a lot to atone for. I wasn’t very kind to…,” he trails off. He makes eye contact with me. I won’t steal his atonement.

He’s having a hard time meeting my gaze, but bless him, he keeps returning to eye contact. He tries again. “I wasn’t kind to people I didn’t understand. I wouldn’t have—; 25 years ago you wouldn’t have been welcome in my home.”

I don’t nod, don’t break eye contact.

“I was thoughtlessly cruel. I voted for, and wanted, your rights to be taken away. I said words I won’t repeat again. I am sorry.”

He sits up and clutches my hand.

“Duella, I am sorry for believing you were less than simply because you are a woman instead of the man that we thought we saw. I have tried to make up for the hurt I have caused. For everything I’ve destroyed. I want to thank you for being part of my apology. . I don’t think I can thank you enough.”

The tears are rippling out of his blue eyes now.

“I, Duella Hernandez, accept your apology. I look upon your works and forgive you.”

Our foreheads meet and some of my own tears escape. We pull back at the same time and blink back our tears.

“I’m crying too, for all the people who have never sunk their fingers into the loam of their mother. For the ones who are born in space who will never know her embrace, never feel our connection to something more than human.”

“Well, those apology trainings sure are effective.” Caiden says, and we both start laughing.

“Right?! Thank god for the community centers or we all would’ve killed each other by now,” I quip. “Besides, you weren’t that bad or you wouldn’t even be here.”

Most of the men had gone up to space, hunting for other planets and people to suck dry while being kept warm at night by the engines of their robowives, robogirlfriends, robomistresses.

Those of us left on Earth either chose to stay or weren’t invited. Caiden chose to stay. I wasn’t invited.

He snorts, “Nobody who left was worth more than two cents.”

But they are gazillionaires in Bnki$t@ or whatever they’re calling the new moon-based currency. They took all the “money” with them when they left, digital vaults full of nothing you can see. They left everything “useless”–trees, soil, the Earth, each other.

We’ve done away with all that now, but the old timers still use expressions like this. In a generation or two it should all be forgotten. Now even teaching the youth about the ways things used to be is difficult–they can’t wrap their heads around health insurance or inaccessibility of midwives and doulas or the illegality of soil burials, bathrooms, borders.

He coughs now, a truly ugly one. Dry at the beginning, rattling like leaves, then wet, a garbage disposal. His face turns red, then white, then red again. When it’s over, he collapses and doesn’t breathe for one count, two count, three count, four cou-

He coughs again, a little one, then begins to breathe. “I think,” exhale, “I think I’m going to go now.”

And he does.

****

Rebecka does not take the news well. There’s the disbelief (But he was doing so well today!), the denial (Are you sure? He sleeps so deeply now, take his pulse again!), the anger (Why didn’t you call me, I would’ve come running!), the sobs as she runs into her room. I don’t say much during this, it’s better to give time than force calm. I’ve already messaged Dina, the Comforter picked by Rebecka months ago. She’ll be here soon, with baked goods and her warm, maternal smile. In cases like this, where Rebecka is the only one of Caiden’s children who forgave him, outside comforters are so beneficial.

Dina was a single mother of five kids. In the old world she was hated for being on food stamps before the program was shuttered. She worked two jobs, missed birthdays, graduations, just to put a meager amount of food on the table. Her rent crushed her. She was called an unskilled worker, although her chilaquiles were unmatched, she could coax a smile out of anyone, she mourned with those that mourned, she made her children feel special and loved, she was generous when she could hardly afford to be.

Now, she is a Comforter, a prestigious position. Her previously unpaid labor has made her rich in the new gift economy. They told us that universal basic income would stifle us, that there would be no progress or incentive to do well. They forgot that we naturally reward each other for a job well done with gifts and Dina always does the job well.

I start the next phase of my work. I close Caiden’s eyes and cover him with lavender, chamomile, jasmine, and lilies. This makes the corpse look peaceful and a smell inoffensive for the short viewing period. The peppermint oil I rub into his skin helps.

Then digging. It used to be my least favorite part, but I find it cathartic now, all this movement after weeks of sedentary waiting. The spot Rebecka picked is close to the house. It’s a nice spot for a garden. The sun will nourish the plants without burning them.

I finally finish the hole several hours later. Rebecka and Dina are with Caiden’s corpse. They don’t need me. I try not to disturb them as I leave, but Rebecka calls after me that they’ve already finished preparing the soil. I take the bag from Rebecka and return to the hole. Here, I work the soil infused by Caiden with his story and blessed by Rebecka with her hopes for his spirit into the soil of his grave.

It’s a beautiful ritual, yes, but it’s also introducing new bacteria, protozoa, actinomycetes, and microscopic amounts of fungi into his resting place. My handling of it, Rebecka’s handling of it, Dina’s handling of it, Caiden’s handling of it, all of us sharing our unique biomes, will imbue this soil with the biodiversity it needs to thrive.2

****

I sleep deeper than I have in weeks. There will be no desperate late night calls or texts and my body is exhausted from digging Caiden’s grave. When I wake up, my muscles are delightfully sore. It’s a reminder that I’m alive, that I’m growing, that I’m strong.

I have a lot to do today. First packing up the rest of Caiden’s soil, then the funeral, then the burial. It will be another late night and I rub copious amounts of the salve that my friend Morgan made for me into my skin. It smells delightfully of lavender, eucalyptus, and capsaicin, beneficial when you spend your day with a corpse, but it’s also a pain reliever and anti-inflammatory.

The process of packing the rest of the soil into canvas bags goes well and I get it all loaded into my truck before noon. It’s dark, rich, primed for its next step. It’s one of few positives to a drawn out death.

My truck is not quite as primed for its next step as the soil is. It always takes a while for the solar cars to start up. It’s a worthwhile sacrifice but secretly, I do miss the instantaneousness of the old gas cars. Sometimes.

When I arrive at Rebecka’s house, Dina and Tahani’s cars are already here alongside a few I don’t recognize. Tahani and Caiden met when they were providing rescue and support services for the Huntsville flood around 25 years ago. They’ve been best friends ever since, and he lovingly referred to himself as Tahani’s apprentice even though he was almost two decades older. Caiden chose Tahani as his Organizer. I’m glad she’s here.

I drive past the house, as close as I can get to Caiden’s grave site without disturbing any of the existing plant life. I wrestle the smallest bag of soil out of the truck bed and haul it to the grave. I can already see ants, beetles, and a few worms scrounging in it and a smile finds itself on my exhausted face. Perfect.

I pour most of this bag out and get down on my hands and knees, kneading the new soil into the old. I’m getting filthy, but that’s why I brought three changes of clothes along. The bugs crawl around my fingers, my calves, but I don’t swipe or shake them away. We are all part of the same divine task, and that holy feeling rushes down to my stomach. I’m smiling, but I’m crying too, for all the people who have never sunk their fingers into the loam of their mother. For the ones who are born in space who will never know her embrace, never feel our connection to something more than human.

****

“Caiden’s life shows us there is potential for growth, atonement, and hope in all of us. His legacy is one of metamorphosis.”

The funeral begins with stories and laughter, but I’ve never been all that comfortable with crowds. My part won’t take place until after Caiden’s body returns to the earth in about a year’s time, time for reflection on what we’ve lost and perhaps what we’ve gained.

I seek company of a more silent type.

Caiden is still in his bed, but is now wrapped in sheets to keep his seepage and smell contained. His mouth is kept shut with a strip of cloth tied from his jaw to the top of his head. His eyes have been glued with honey and his skin smells of peppermint oil and lavender, permeating with a bit of the sweet scent of rot.

I pull him into my arms in an adjusted version of the fireman’s hold and start his final journey into the woods. I lower him into his grave and cover him with alternating layers of soil and leaves. This used to be illegal, but so did my going to the bathroom in most public places. Now formaldehyde is the illegal substance.

I leave the softest parts of him uncovered for the scavengers that need it; their mastication and the bacteria they bring will further break his body down into the essential parts the soil needs. I read him his favorite poems and memories from his end of life journal as the insects begin their work on him.

****

Two weeks pass and the process is going well. I’ve been in a season of rest, but once this is finished, I will again be assisting someone in their season of change. This time will be a birth, in the cyclical way of nature. I wear a fabric plague mask with lavender and peppermint sachets to cut the smell. The exposed parts of Caiden’s corpse have flattened and the grave has sunk in around him. The insects dance around him in a frenzy. Two full generations of flies have passed, the maggots here now are the great-grandchildren of the flies that first settled on his corpse. Life goes on.

I take the final bag of soil from where I’ve left it and start piling it on the grave, finally covering all of what used to be Caiden. I cover the soil with more dead leaves and mulch.

In springs to come, Rebecka, maybe even Phoenix, will come here and plant the seeds Caiden chose. In autumn, they will harvest the squash, compost what’s left, and plant again when warmer weather comes. An eternal rebirth.

****

The seasons pass in births and deaths, marriages and divorces, menarches and menopauses, until it is time for the first butternut squash harvest from Caiden’s grave and for the mourners to return.

My eulogy starts as all such gatherings start now. “My community.”

“Your community.”

Human solutions often re-articulate the problems they attempt to solve. I always find it laughable that we think we can fix the massive harm we have caused with the same conceptual models that initiated the harm. The more humble thing to do is to see our species as profoundly juvenile. The dynamic homeostasis of the Earth is much better equipped to handle the mess we’ve made. What does atonement involve? Is it ritual? Is it the cessation of extractive practices? Is it developing species humility? (Annotation by Sophie Strand, Guest Editor)

This is a beautiful complexifying of community, underlining the communal gift economy mentioned in relation to Dina. We weave together relationally with ritual and comfort, but also very practically with every inhalation and microbe-infused touch. The death ritual not only involves human beings but their biomes and holobiont participants as well, showing us that a gift economy is one that knows our greatest gifts are more than human. (Annotation by Sophie Strand, Guest Editor)

Bringing Sci-Fi Down to Earth…

Tractor Beam is a soil-based Sci-Fi publication that explores speculative ideas around farming, food, earth sciences, and beyond, imagining a positive future here on Earth (in the earth). Our goal is to connect people to regenerative agriculture and soil health in a meaningful way. We call it “soilpunk.”

Hey, great read as allways, this exploration of how our complex, imperfect lives truly transcend death feels profoundly important.