Written by: Phoebe Wagner

Illustrated by: Cynthia Alfonso

May, 2026

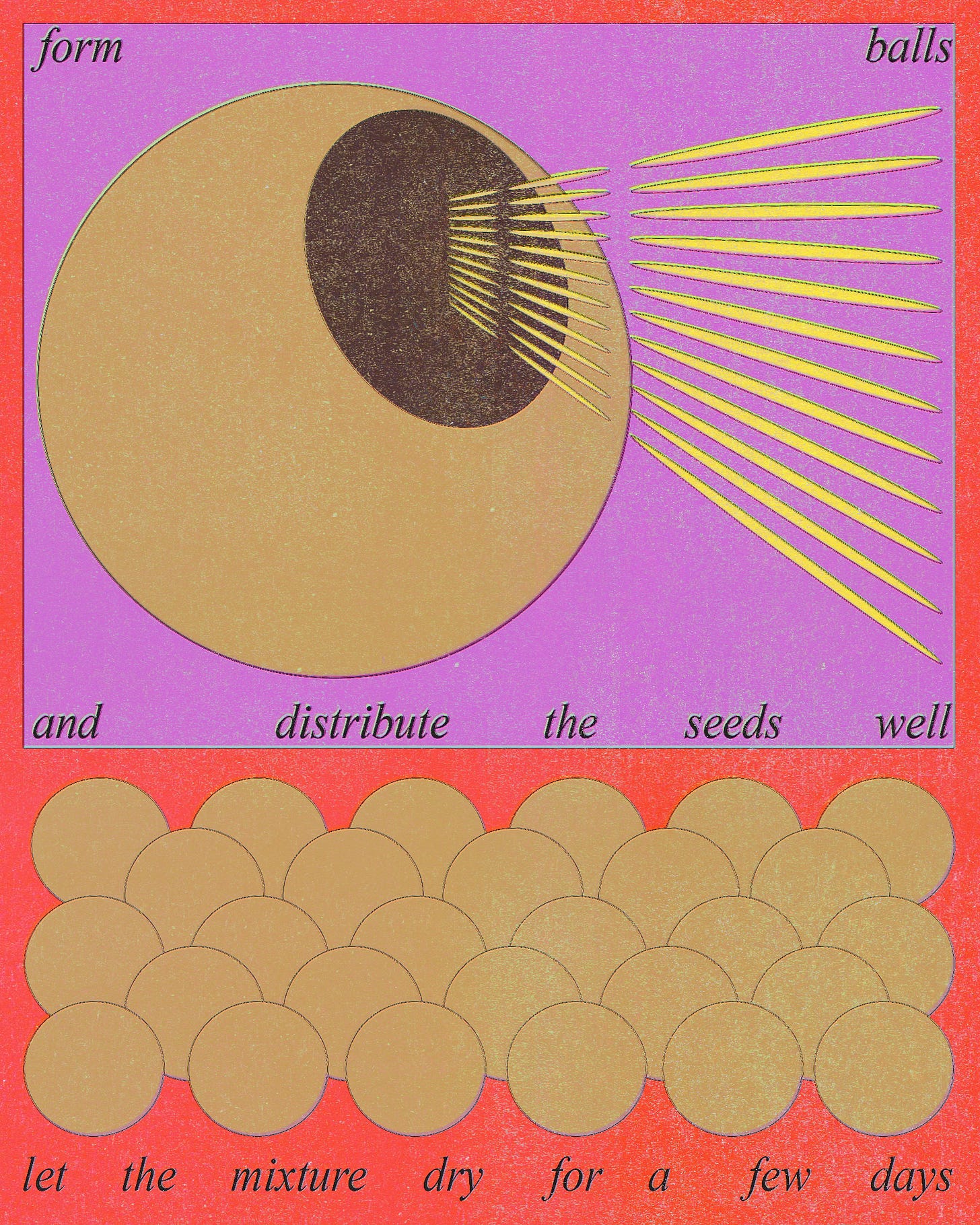

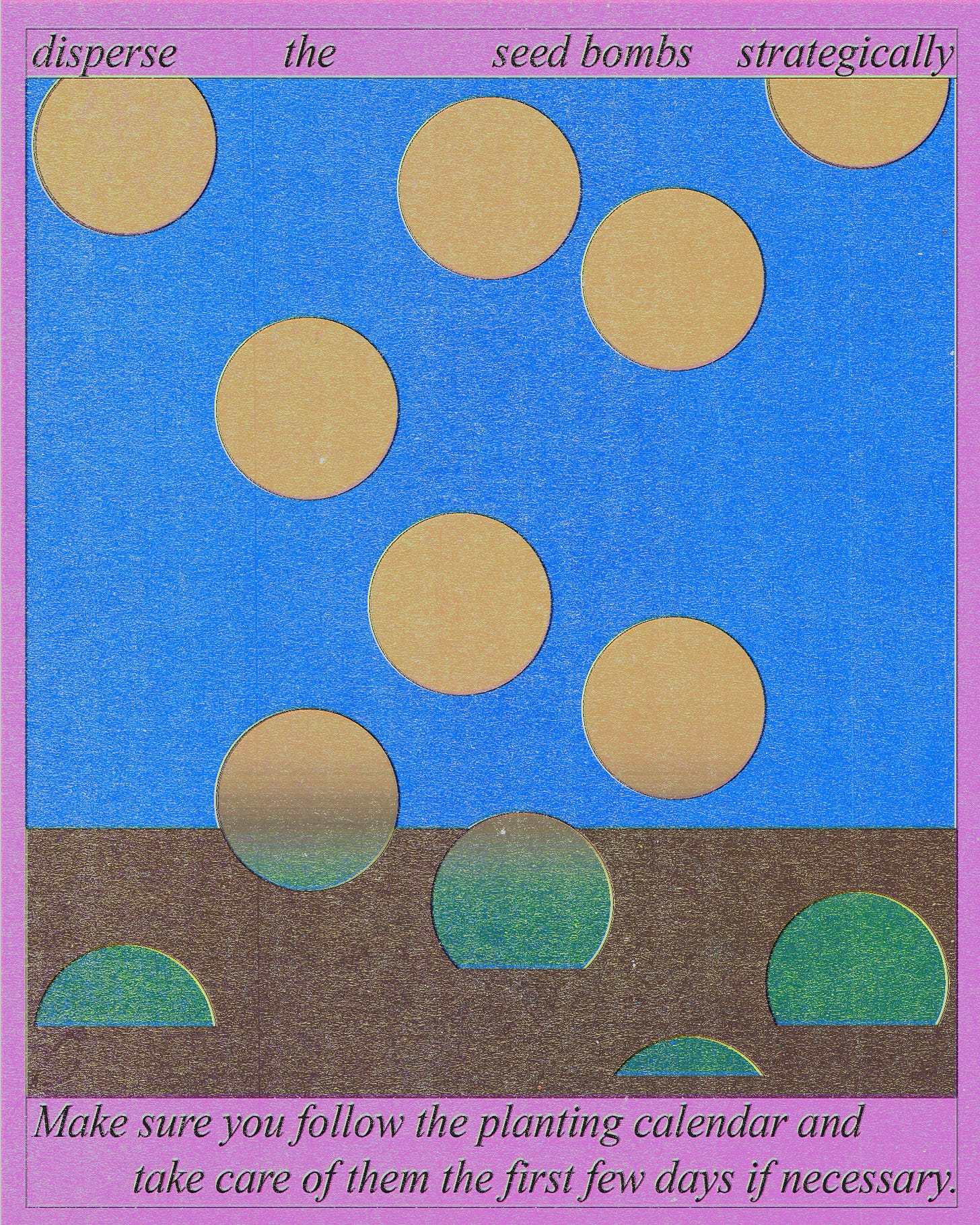

Drew flicked the seed bomb into the empty lot as he skated by. The little ball of seeds, compost, and clay burst in a silent puff. A few years ago, the lot had been his favorite pizza place, with an X-Men pinball machine in the back corner, but it flooded. Second Street wasn’t supposed to flood. Lots of things weren’t supposed to happen.

The city had torn down the soggy building, then—nothing. The grass grew. Sometimes somebody mowed it. Tree of heaven grew, got cut down, grew again.

At least these seeds were the right species. He’d spent a few hours researching different seed sellers online to make sure they weren’t being drop-shipped from some GMO greenhouse. Spring of his senior year, he tossed the seed bombs on the way to and from school. The lot greened, but he wasn’t sure if they were his seeds yet.

During the last week of school, his art teacher asked him to stay after class. Mr. Jackson handed him a sketchbook and what he guessed was another small book, wrapped in the brown paper abundant in the art classroom.

“Not sure if you heard, but I’m leaving,” Mr. Jackson said. “We were worried, with the new governor. Well, my husband and I can’t stay. There’s already a law being proposed.”

Drew felt his throat tighten. “You—you were my favorite teacher. Just so you know.”

Mr. Jackson picked up a piece of purple chalk, crumbled it in his fingers. “I’m only telling you because you’re graduating and because I don’t want you to think it was this place. We loved it here. We wanted this to be home.”

He jerked his head up. “This place sucks. I’m glad you’re leaving.” At least someone was getting out.

“No, no, that’s not what I’m trying to say.” Mr. Jackson sighed, then tapped the small, wrapped book. “Maybe this will help. And don’t stop drawing and skating and doing all the things that bring you joy, huh? It’s easy to fall away from those things when you get a job. Try to hold onto them.”

He nodded. “Okay, Mr. Jackson.” He hurried out the door, clipping his shoulder on the frame. His body felt wrong, all pent up, a joint that needed to pop.

He made it outside and bent over, hands on his knees, for a few deep breaths. Unlike last summer, which had stayed cold until almost July, the heat started in April this year. The county was already in drought.

He unstrapped his skateboard from his backpack. Falling into the rhythm of his board, the sidewalks he knew the highs and lows of like his favorite song, eased some of what others would call the sadness in his chest—except sadness wasn’t the right word. He felt sad when his favorite band broke up or when a YouTuber he liked quit. This feeling was like when he saw what happened to the pizza place and all of Second Street or when he realized no college was going to give him the type of financial aid he needed. Sorrow, he thought, as he stepped off the board, popping it into his hand.

The seed-bombed lot had turned a weak green. The heat and drought crisped the new plants, but they still grew.

He glanced left and right, but people didn’t linger on the remains of Second Street. He squeezed into the lot where the fence curled back from an abandoned building, an old barber shop.

The first flowers had been small, yellow ragwort, according to his photo ID app. He kept meaning to go by the library and pick up a real identification book, but the app worked so much faster.

More flowers dotted the yellowish grasses. Some were the invasives he saw in the highway cuts and growing out of sidewalk cracks: dame’s rocket and crown vetch, according to his app and what he read online. He still thought they looked pretty. Better than the tree of heaven growing in the corners.

But some of his seeds had flowered: the golden ragwort grew tall and spare, but the yellow specks of color made him smile. They’d grown first, and he’d cut a small piece, pressing it in his sketchbook.

Today, he wandered through the lot, hoping for the milkweed to bloom. His seed bombs had included common milkweed and butterfly milkweed. He’d learned about them in his AP Biology class. The lot wasn’t the same as an open field, but the closest thing in town. Maybe some butterflies would find it. A lot of the plants had sprouted, but the common milkweed was easy to recognize because of the broad leaves.

He sat on his skateboard by the tallest milkweed stalk. He had this idea of buying some of the cheap chalk pastels from the art store and making a smudged, colorful sketch of the lot. He wasn’t sure if it would work, but once the flowers really started blooming, he wanted to try.

Today, he just drew the milkweed’s leaves in the new sketchbook.

With school over, it was two weeks before he visited the lot again. He brought some colored pencils, a graduation gift. Late June, he hoped the lot might be transformed with color, just like the old pizza place, with the flashing pinball lights, the stained glass art the owner’s wife made and sold in the lobby, the bright red booths.

Over his music, a construction vehicle beeped. Two orange cones closed the sidewalk.

He pocketed his earbuds and walked the final block. His heart hammered, and he already braced.

A backhoe sat on a dirt pad. The fence had been repaired, and a local construction company advertised they were fixing up Second Street. Luxury condos, of course.

He paused only for a moment, then kept walking until the sidewalk opened again. He threw down his skateboard and jumped on. The rhythm gave him somewhere to hide. He shoved, hard and fast, away from this new dead zone.

June, 2027

The new punk coffee shop, Odo’s, advertised a book club. The small, orange book, Mutual Aid, was the same one his art teacher had given him, which he hadn’t read yet. Drew had packed away the book and his favorite art supplies to go sketch at the park the third week of summer, but he’d gotten called into work at the gas station. He’d never unpacked them in the past year, but he’d brought the bag on a whim.

Places like this weren’t supposed to get punk coffee shops. They were too red, too worn out, too old. Who would even go? the local news report asked.

He actually felt out of place when he stepped inside. Everything felt too colorful, too loud, even though he recognized the punk music playing. He fumbled his card, his board under his arm, as he ordered a black coffee. The person behind the counter had an undercut and a they/them pin on their black T-shirt. They looked familiar, like he’d seen them at a show, but he’d stopped going to those, too, picking up shifts at the gas station instead.

They handed him his black coffee in a random mug (The Best Grandma). He dropped off his bag and skateboard at a table and turned to the riot of color on the walls. The color had been pulling at the corner of his eye since he walked in, but the sinking anxiety of feeling out of place, that he was just some poser now and shouldn’t be here, had kept him focused on ordering and scuttling to a corner.

But now, now he felt at home.

It was the meadow. Repeated over and over in large format pictures. The photographer had captured the meadow in several stages—including the backhoe killing it. The flowers popped in bright pinpricks of color, and he found purple lupines near the fence, the seeds he’d been most excited to plant from the online pictures.

The relief swelled. The meadow lived. He hadn’t gotten a chance to sketch it, but somebody had kept the memory, like the plants he still had pressed in his sketchbook.

He pulled the untouched sketchbook from his backpack and drew the meadow with the photos as reference. Next time, he’d bring the colored pencils.

****

Two weeks later, Drew sat with the book club. He worried it would be like his English classes, but nobody raised their hand. The conversation moved so fast he lost track of where they’d started.

The discussion turned to what they should do. Some people talked about community meals, others wanted a community garden. Another group talked about a bike repair clinic with bike lessons.

And suddenly his mouth was opening: “The bike clinic could offer compost pick up. For the garden.”

He’d only listened for the past hour other than saying his name, so they all stopped talking and looked at him. He’d always hated that in school, too.

“Yes,” said an older woman with a purple flowing dress. “It’s all connected, isn’t it? Or it could be. The bike clinic collects compost for the community garden. The community garden comes together for a community harvest meal for all.”

“It’s all connected, isn’t it? Or it could be. The bike clinic collects compost for the community garden. The community garden comes together for a community harvest meal for all.”

“I don’t know much about bikes,” Drew said, “but I can ride, and I can learn the rest.”

Three projects were sketched out by the meeting’s end. First, a harm reduction group, which felt especially necessary to them all after a bad batch of heroin had caused people to overrun the ER. The opioid crisis wasn’t in the news much these days, but they still felt the impacts, especially in the flood’s hopeless and jobless aftermath. He’d heard about the ER visits, the bad batch, during his night shift at the gas station, and had hopped on Facebook for the first time since graduation. By the end of the night, two of his former classmates were dead.

The strongest voice for the harm reduction group had been a familiar face, and he finally placed her from his freshman year, a senior named Sara. From her familiarity with the baristas, she either came here all the time or she worked here.

The community garden became a two-part project after an almost heated discussion between Charlie, who he’d never met until now but always saw walking around town or chatting with the old guys sipping hot coffee at his gas station or McDonald’s, and a woman who gave off “I live on the hill” vibes. There was one Tesla in the parking lot, and he bet it was hers. The woman, Didi, wanted the garden, but Charlie said they had to deal with soil contamination from the flood first and, besides, people were overflowing the foodbank. Did she expect starving people to garden in their spare time?

The woman in the purple dress, Joan, had cut them off: “Perhaps you should work together to do both. Meals as often as can be organized and, when available, the meals can include garden produce, or it can be handed out with the meals.”

Charlie’s face flushed, but he nodded. “Sure, sure, I can live with that.”

Didi sipped her coffee from a Yeti travel mug, then dabbed her lips. “If that’s what it takes for this place to finally have a community garden. You know there are other benefits than just food, like—”

Charlie tilted back his chair. “We know, Di, we know.”

The other woman, Joan, turned to Drew. “What about the bike project?”

It hadn’t been his idea, so he glanced at the guy on his right, Louis, who he knew from skating. In his late thirties, worked at restaurants and around town, always on his board or road bike. Louis pulled back his locs, then let them fall around his shoulders. “I can take that on, I think. The library has been at me to hold a bike repair workshop. We can start there.”

“I’ll help,” Drew said. “I mean, I’ll have to learn, too, but I can—I don’t know—carry stuff or whatever.” God, that sounded so silly. He pretended to sip from his empty coffee.

Louis grinned at him. “Good, man, thanks.”

“All right,” Joan said, making a note on a beat-up legal pad. “Louis and Drew on the bike project.”

July, 2031

Every summer was the hottest on record, but this summer felt especially bad. Drew preferred heat to cold, but this heat parched his skin, made him feel dry inside, like he needed to go soak in a cold creek. Usually, after collecting food scraps, he did.

Today, he walked his bike and trailer up the worst hill to the garden lot. Charlie met him at the gate and held it for him. He’d soaked through his shirt, and his tattoos were dark smudges through the wet material. “I was getting worried. About to send Cassie out in a car to look for you.”

“Ah, it’s not that hot.” He checked his phone—he’d missed two calls from Charlie.

“Sure as hell is.” Charlie took the bike from him and wheeled over the trailer to the compost station while Drew wet himself down with the hose. They’d recently received grant money for shades, so the garden space looked like some strange sculpture project, with wooden structures swiveling sails to block the worst noonday sun.

Sara, from the harm reduction project, and Kris, a new volunteer, unloaded the scraps with Charlie’s help. Drew willed his legs to go join, but the shade and water felt too good. He checked the thermometer on the side of the shed—105. He texted Louis about what supplies the cooling locations needed, and Louis shot back: Didn’t Charlie tell you?

Drew jogged over to the dry compost pile. Sara watered it while Kris and Charlie flipped it with pitchforks. “I’m going to take water to the cooling centers—anything I should know?”

“Yeah, fuck the mayor,” Kris said.

“He shut down the cooling centers,” Charlie said, “with the support of city council, except Didi.”

“Can—can he do that?”

“Probably not,” Sara said, “but who’s going to stop him?”

Drew’s shoulders slumped. A cicada screamed, somewhere over in the fruit trees. The gurgling hose reminded him of his childhood, running through a sprinkler—all the air-conditioning he’d taken for granted.

“What about Chuck’s church?” he asked. The Episcopalian church offered its air-conditioned sanctuary as one of the locations.

“He rents it,” Charlie said, “and the city bought it a few years ago to ‘support local organizations’ and offer reduced rent.”

Drew wiped his sweaty face on his shoulder. “Shit, I forgot.”

Charlie drenched himself with the hose, and Kris followed his example. Sara wet the towel around her neck. “He’s keeping it open, anyway,” Charlie said. “But I doubt it will be longer than twenty-four hours. Besides, we can’t accommodate everyone in there.”

Kris checked their phone. “Mutual Aid meeting called at Odo’s in two hours.”

“Great,” Drew said, “that gives me enough time to take a load of water out. I’ll leave it along the river walk and the bridges.”

Charlie took a road bike out of the garden shed. “I’ll join you, take turns.”

The heat sapped their will to talk as they loaded the trailer with donated water. Drew thought about swinging by his car instead, but it wouldn’t get him along the river walk, one of the coolest spots in town, especially under the different bridges. The bike would suit him better.

It wasn’t the first time the mayor or the city council had just decided to be cruel, but he never quite got used to the blow, the anger. Why hurt people? Why make somebody’s life worse? Of course, they always had a reason—tourism, this time. Too many unhoused people clustering in certain spots. Except it wasn’t even just the unhoused. Landlords weren’t required to have HVAC or air conditioning. People couldn’t afford to blast their machines in the heat of the day. Elders and children needed places to cool down. Not everyone could afford to pay a day pass to a gym or buy a cup of coffee or a happy meal. The library would be swamped this week—if they stayed open. This heat was murder on their energy bill, and they couldn’t afford much more of it with their funding cuts.

They coasted past the empty parking lot that had been the meadow he’d planted his senior year. Heat wavered off the black asphalt, and he felt the temperature rise as they passed.

They coasted past the empty parking lot that had been the meadow he’d planted his senior year. Heat wavered off the black asphalt, and he felt the temperature rise as they passed.

August, 2036

Drew, Louis, and a dozen teenage skaters shoveled mud out of the bowl, scraped it off the ramps. No matter how much they hauled away from the skatepark, there was always more.

Of course, it wasn’t supposed to flood here. Just like Second Street wasn’t supposed to flood.

Louis kept it light, joked, played punk music from his phone, then from a bluetooth speaker he scrounged up. Louis’s home was gone, so Drew didn’t know how he stayed so even. Drew kept tearing up, wiping at his face and hoping the others would think it was just sweat. He hadn’t lost his home, his family was okay, his girlfriend Sara’s family was okay. But the skatepark—it felt like losing his home.

Part of what made his life mean something was the park. When Didi had passed away two years ago, she’d left a sizable amount of money to the Mutual Aid project, which had shocked most of the members. She’d often disagreed with them, but she always said they helped, which was more than most of the charity organizations in town.

Drew and Louis had proposed to expand the bike project to include a skate/BMX park, which would also offer lessons and community events. With some freelancing graphic design on the side, the skatepark, and keeping things cheap by living with a roommate, he’d carved out a comfortable life. He’d never be rich—and retirement wouldn’t be great—but he had a life on his terms, working with others.

Now it felt so tenuous, the rope so frayed. He felt climate change growing worse every summer. Each winter, the community garden planned how to adjust, how to survive the worsening heat, what plants and food to grow. They thought long term about what trees would be better suited for the area and how to serve the soil so the next generation would have spaces to grow.

Part of that long term thinking had been classes and community knowledge sharing. Each of the projects—the garden, the bike project and skatepark, and the community harm reduction group—had started teaching programs. The teaching went both ways, too. Their town was changing as climate refugees came from the southwest and heat island cities like NYC and Newark. The coffee shop hosted Spanish classes and English classes as well as Know Your Rights training as the increase in Latine people also meant an increase in ICE raids, regardless of their status.

Each winter, the community garden planned how to adjust, how to survive the worsening heat, what plants and food to grow. They thought long term about what trees would be better suited for the area and how to serve the soil so the next generation would have spaces to grow.

As he heaved mud into a wheelbarrow for the hundredth time, the nihilistic punk side of him said, what good had it done? In the wake of the flood, there had been a massive ICE raid. He wasn’t on the rapid response team, but his girlfriend Sara was and said it was bad. They should’ve known, Sara said. They should’ve been prepared for this double tragedy.

The one bright spot was the flood had missed three of the four community gardens, and it was harvest time. In preparation for the storm, they’d picked as much as possible, which now needed to be eaten. After cleaning the skatepark, Drew went each evening to help prep a community meal. People came to the different garden locations to eat and talk in the shade since most places still didn’t have power. People laughed and told stories. The second night, people brought out their guitars or harmonicas or violins. Drew tried to balance finding a glimmer of happiness in all the wreckage with the knowledge that members of their community were gone—dead, detained by ICE, displaced by their new homelessness.

Drew and other bike project volunteers also biked fresh meals to the elders who couldn’t walk the broken streets. He made sure they had everything they needed for the night and took requests, which the Mutual Aid group did their best to fulfill from their funds. All this kept him busy and tired enough to sleep at night instead of staring at the ceiling, anxious for the sound of thunder.

A few weeks later, he and Louis stood with their boards on the lip of the bowl. For once, Louis was teary-eyed. With a whoop, he dropped in. Drew watched him glide with a fluidity he could never achieve. Louis could have joined a crew somewhere else, if he’d left town, gone to Philadelphia or some other city. Instead, he’d stayed, which had always made Drew feel better about his choice to put down roots here.

Drew dropped in behind him, following him around the park, mirroring his moves.

September, 2046

Summer didn’t end in August, or even September, anymore. He sweat in the muggy air on the last day of September, staring at the parking lot that had once been his favorite pizza shop. A developer branch of a big box internet shipper had bought the whole abandoned street, planned to turn it into some sort of warehouse district with apartments above each warehouse. Sounded a lot like a company town, to him. The plans shown at the last city council meeting had featured so much asphalt, concrete, glass and steel. Not a single park, not a single street tree. And people were expected to want these apartments? At the low cost of the rental—for employees—people would flock to the jobs. And if you couldn’t pay one month, would it be eviction? No, he imagined it would be taken out of the next paycheck.

When he’d graduated and skated past the meadow his seed bombs had helped create, he’d never imagined this life. He’d struggled to make connections in high school, and his parents had felt distant, exhausted. Yes, they loved him, but he wasn’t sure what parts of him they loved, or if they could love all of him.

Now, he understood them better. He’d had two options as they aged—put them in an elderly community an hour away or move back home. He’d chosen to move back home.

Just like childhood, he skated by the parking lot on his way to the community garden every day. Sometimes, groggy with sleep, when he opened his eyes to his childhood ceiling, he panicked about forgotten homework. But surrounded by his old punk posters, his ripped black jeans that no longer fit, the old pair of chucks that still did, the dusty desk—he remembered the kid who threw seed bombs.

Surrounded by his old punk posters, his ripped black jeans that no longer fit, the old pair of chucks that still did, the dusty desk—he remembered the kid who threw seed bombs.

In an old desk drawer that stuck unless you pulled just right, he found the zine that had taught him how to go about building seed bombs (placed on a stack of old condoms).

That kid had been restless inside him all night after seeing the construction signs, so he strapped a shovel and pickaxe onto his electric motorcycle and rode to the parking lot. He loved his electric motorcycle for how quiet it was, the engine a soft whine. The clank of the tools was louder. He told himself the tools were “just in case” but the recently graduated senior still inside him said what they were going to do.

The parking lot had been unused and left to crack and heave. Since the floods, no revitalization project had managed to bring business or people back to the area. It still smelled dank, as if the water and mud had never really dried from all those years ago. Maybe this big box store would fail, too. Better to let the so-called weeds take back over than what the city had planned.

A big section had heaved near the back edge, and ragwort grew between the cracks. He apologized to the plants as he hefted the pickaxe. He didn’t think, didn’t doubt.

He’d broken up parking lots before as the community garden project expanded, buying up empty lots. They now ran a free community-supported agriculture and also donated to the food bank. The bike project had also expanded—recycling and compost pick up, mountain bike camps, repair lessons, and bike camping along a rail trail that spanned most of the state. The skatepark hosted summer camps and after school programs, queer skate meetups, multiple youth tournaments. Louis had stepped back to open a skateboard shop, so Drew managed the park entirely. It was the type of place he’d deeply wanted as a teenager, and he felt proud he’d helped bring it into reality.

He finished hammering apart the back left corner where greenery, watered from the nearby stream that was finally flowing again after the hottest summer on record, crowded the edges, broke apart the unwelcome surface.

He clambered down to the stream with his water bottle a few times, soaking his slip-ons, and watered the exposed corner. The squelching of his shoes sounded extra loud in the gray dawn. He was too old to be staying up all night, but he felt good, exhilarated. He’d planned to call in a mental health day but decided to go in for a few hours to the skatepark, anyway.

He pulled out a packet of seeds from the community garden, late fall flowers: sage, coneflower, mums. The last day of September was really too late, but with the weather so out of whack, who knew what might grow?

Stay tuned…

Thanks for tuning in to Day 2 of 12 days of climate fiction! Make sure you’re subscribed to get the first look at all of Issue 2’s stories as they drop on our website, right here on Substack and in your inbox!

Know someone who is an avid sci-fi reader, passionate about climate work, or loves to get their hands dirty in the soil? Spread the word and share our newsletter. And give us a follow on Bluesky and Instagram to stay connected on the latest. Let’s grow a better future together.