Written by: J. Rohr

Illustrated by: Anna Degnbol

Grady couldn’t find the right tool. Grumbling acidic curses, he shuffled around the workshop. Normally, he prided himself on everything being organized. Things had gotten sloppy lately; he had gotten sloppy lately.

Under a pile of stray circuit boards and clipped wire bits, he found the elusive implement. Grady picked up the multipurpose FPV prop tool. The initials B.Z. were crookedly etched into it—Bernie Zając, his grandson. Sighing, he returned to repairing the damaged drone.

The main issue involved a burnt-out circuit board. Something his old hands could fix blindfolded at this point. Lord, if his own granddad could see him now. The fool child who barely got an old push lever toaster to work soldering wires and swapping out spent chips. Returning to the drone, he decided to replace the dying battery too. No sense in sending it up only to have it come right back down again, especially after the fall it already took. The secondhand board fried, and the soaring contraption dropped like a stone.

His husband called it a grim omen over lunch. Grady considered it an annoyance.

“They fall, Marty,” he said. “Happens every couple of months.”

“Seems like it’s happening every couple-a weeks is alls I’m sayin’,” Marty said, munching on tacos de gusanos de maguey.

“We can’t afford a fresh swarm,” Grady said.

“I know, I know,” Marty said, holding up his hands in surrender. Then he added in a gruff voice playfully mimicking Grady’s gravelly tone, “Better somebody fix what’s broke.”

The old farmer frowned. Marty winked, and Grady grinned. He couldn’t be mad at someone for knowing him too well. They changed to sunnier subjects.

He spent most of the morning hauling and fixing busted drones. By midafternoon, all except one returned to the sky. None of them possessed exactly the same problems. Fortunately, Grady was familiar enough with their myriad malfunctions to deduce and repair the issues lickety-split. Fried boards, melted wiring, and damaged chips were soldered, switched, and restitched, so to speak. All of them bordered on a need for new batteries, now or tomorrow; better to do it today.

Always the pinchpenny, Grady got into the habit of making his own batteries. Too many farms bled out thanks to that secret expense. Descended from a long line of scrimpers going back to survivors of the first Great U.S. Depression, he prided himself on frugal self-sufficiency.

Descended from a long line of scrimpers going back to survivors of the first Great U.S. Depression, he prided himself on frugal self-sufficiency.

Yet, it was his grandson, Bernie, who possessed an almost preternatural sense of how to work the battery maker. No matter how closely Grady followed the recipe, the art of it eluded him. Granted, his organic batteries worked, but that boy’s lasted a lifetime. At least they seemed to. Grady didn’t need to replace any of the kid’s electric cells until well over a year after Bernie left the farm.

At the assembly station in the workshop, Grady tried not to think about the lost boy. Yet, his memories housed an intrusive ghost, the little kid who stared at the crops in plain disinterest. Grady recalled how Bernie grinned whenever he heard the day was done. Forcing himself to focus, the old man squinted at a recipe note on his smart glass. He put together the quinones, polyaniline, and anthraquinone to compose a cathode. Then the lithium-coupled redox-active organic compounds. Finally, Grady dealt with composite materials made of conductive organic substances, the whole electric burrito wrapped up in a thin-film slurry coat. His grandson left with nothing except his winter jacket; he thought the boy would be back before the sun went down.

The battery maker pinged. Grady replaced the spent cell in the drone, tossing the dried up electric well into the recycler.

“Waste not, want not,” Grady muttered.

All this saved them thousands a year. While the farm still flirted with the razor edge of ruin, the danger of a crippling slice never came close. The old man sighed. At least it wasn’t like the debt that drove his dad around the bend. Thank Jesus, Allah, Buddha for subsidies from a sane government. Naysayers called it rural socialism. Farmers called it financial relief. Whatever label it deserved, Grady considered anything that sent the suicide rate down a good thing.

Propeller nuts refastened, the downed buzzer would soon be able to return to the swarm. He gave the dented device a gentle pat.

“Fly high, Icarus,” he remarked. “But mind the sun.”

“Fly high, Icarus,” he remarked. “But mind the sun.”

Then activating an app in his strip of smart glass, Grady turned the drone on. It sputtered to life in seizures anyone unaccustomed to would find disconcerting. The machine’s disdain for resurrection duly noted, Grady gave it instructions to rejoin the swarm surveying the farm outside. The hovering machine slowly drifted to the door, then up into the sky. It flew at a pace reminiscent of Robin Block, an aimless cloud of cannabis smoke drifting around town, floating through life as if there wasn’t important work to do, one of Bernie’s high school buddies whom any decent granddad could see was infecting others with indolence. It made Grady snort.

It also made him wonder if the artificial intelligence controlling the swarm needed another reboot. Every few months the monitoring software developed personality traits closer to a rebellious teen than a dutiful farmhand. The swarm still did its chores without question, but an increasingly obvious hesitation crept into the following of commands. The A.I. seemed more and more bored monitoring soil health, checking moisture levels, and watching for harmful insects.

Of course, Marty chided him for blaming the ghost in the machine.

“A.I. is still in its infancy,” he would say. “Can’t blame a kid for being a kid.”

To which Grady often replied with a characteristic monosyllabic utterance. Their intimacy made that enough. Perhaps he simply wished people could be rebooted, reset to some factory standard as easily as artificial intelligence. Especially when the seed of a damn fool idea rooted in their noggins.

Perhaps he simply wished people could be rebooted, reset to some factory standard as easily as artificial intelligence.

Kicking a clump of dirt, he sauntered out of the workshop. For a moment, he observed the swarm moving like precision fliers. Some rained down water in exact amounts. Others dusted the crops with fertilizer.

Grady checked on the ammonia synthesis reactor. About the size of a shipping container, it resided at the other end of the field. Nearby, automated stations refilled fertilizer drones, coordinated by the A.I. regulator. Connections to the reactor shunted heat from the process into Marty’s greenhouse where the couple grew their own private stock of edible plants.

Grady paused to inspect the connection between the farm’s solar panels and the ammonia synthesis reactor. The various conduits showed the usual signs of decay. He found everything eroded with time. Sometimes quicker with the right catalyst. Like an abrasive phrase at the wrong instant—sandpaper words gnawing at fraying threads.

The power connections seemed fit enough to last another year or two. He filed the future expense as tomorrow’s concern. Nothing that would imperil a potential anniversary gift for his husband, coral and jade jewelry made by the Caribbean Renewal Project. Grady saw an influencer wearing the piece, and although the app quickly ushered him over to a digital jeweler, he hesitated to buy the piece until enough cash was in his bank account. Soon enough, he’d see Marty decorated with a display of the beauty of possibility.

Grady chuckled grimly. He had tried to tell his grandson how different the world used to be. Sickly leaves like semaphore displays on ailing trees begging for death. The way the sky got greyer and greyer the closer anyone went to a city. Even where it remained blue, a sheen remained like a slick of oil scum. Water coming out of the tap could catch fire; Grady’s granddad used to light his cigarette off the faucet, cackling at a cynical joke that only he found funny.

The little boy didn’t seem to care.

“But it isn’t like that anymore,” Bernie once said.

“Nope,” Grady nodded. “Things ain’t perfect, but we’re making progress.”

“So it’s not a problem,” his grandson said.

The kid didn’t get it. Grady let the matter drop. It fell like the first, or as honest eyes might see things, the fifth or sixth domino. They spoke less and less, save for sharp words. Then one day some stray phrase severed their ties, and the drift apart started with no way to reel the boy back until finally he was gone. So the old farmer focused on the land. That much he could fix.

So the old farmer focused on the land. That much he could fix.

The terminal for the ammonia synthesis reactor showed it was at the first stage. Grady once explained to Bernie how that starting point involved lithium salt reducing to metallic lithium. This then reacted with nitrogen to form nitride. A water splitter in the system provided hydrogen which protonated the nitride. The resulting ammonia got mixed with phosphorus and potassium while the lithium was recycled to start the process all over again. Bernie said he didn’t care what the machine did so long as it worked, meaning one less thing for him to do.

The system’s digital dashboard told Grady that he needed to top off the nitrogen as well as the water supply. Nothing two taps of the screen couldn’t achieve. He heard the gasping groan of a pump sucking nitrogen out of the air. Then the whoosh of water flowing through natural rubber hoses. It only lasted a few seconds, the A.I. regulator only allowing the precise amount needed so not a drop was wasted.

Grady grimaced. Sometimes he felt like a repair person rather than a soil worker. He remembered the gasoline crisis when his granddad ran out of fuel. The fellow nearly exhausted himself to death trying to till the field, 231 acres by hand. Truth be told, he might have cultivated it all and died shortly after, if neighbors hadn’t convinced him to convert to biodiesel. Everyone who didn’t make the same shift—the world lost them in the rearview.

“Hon?” Marty called out.

“Yeah,” Grady said.

Turning around, he saw his husband leaning out of the greenhouse door.

“How’s the electric flow over there?” Marty asked.

“Fine, I s’pose.” Grady turned back to the terminal. “One sec.”

He noticed power fluctuations. Nothing that made the A.I. regulator worried. The smart software compensated instead of anticipating problems. He heard the next gen might, but Grady possessed zero desire to spend a penny on that. After all, cocking an eyebrow, he could follow any clue as closely as a computer.

“What’s going on with you?” Grady hollered back over shoulder.

“Just some flickerin’ bulbs,” Marty replied. “Thought maybe they were dying, but some I just replaced. They shouldn’t be acting wonky.”

“We aren’t getting as much juice as we ought to,” Grady gritted his teeth for a second. “I’ll check out the solar panels.”

“Thank ya, shug!” Marty rang out singsong before retreating into the greenhouse.

Grady strolled along the shelterbelt. The sun was getting low in the west. The setting orb reminded him of the album cover to “Sunset Signs of Apocalypse” by Carnival of Animals. French progressive heavy rock spiced up by a soupçon of technical death metal. It sounded to him like an industrial grinder like one of those big ones over at the recycling center which ate up drone frames. That didn’t stop him from buying the vinyl edition for his grandson. Bernie loved it. And Grady, despite a preference for more classical country from a hundred years ago, Saint Dolly and Hank III, did enjoy the environmentally themed lyrics. It gave the two something to talk about that didn’t drift into shark infested waters.

Grady found the disc in Bernie’s room after he disappeared. One of a dozen sacred things left behind. The album featured a murky brown, red tinted, smog shrouded sunset. Blood and mud drowning the world. Grady tried listening to it now and again, but he never got beyond setting the vinyl in the laser turntable. Then silently back into the record sheath it went, laid again on the bed as it was found.

The present sunset lit his way to the solar panels. Its colors made him chuckle. He couldn’t help recalling that some folks actually fought clean air initiatives saying smog made the sundown prettier. All it took was one parent, holding up an infant kid, poor child hacking up red handfuls in front of Congress—funny how fast politicians shifted opinions once the news printed blood.

Stranger still, it didn’t take long for people to forget. Grady recalled Bernie’s eyes glazing over whenever grandpa went on about the way things used to be. The chest pains on days the air quality dropped. Lungs aching from sucking in sick air. The water purifiers everyone owned, filters turning unsettling colors as they collected lead alongside all manner of invisible poisons.

“You don’t know how good you got it, boy,” Grady once growled.

“The world’s not on fire,” Bernie snapped back. “You act like I gotta save it from something that ain’t even happening no more.”

“Don’t you get it?” Grady scoffed. “It’s a house of cards, kiddo.”

“Maybe back in your day, but times have changed.”

Another exchange going snicker-snack, severing connections. Grady gritted his teeth. He felt haunted.

The array of solar panels on the other end of the farm rotated. They moved like sun worshippers determined not to lose sight of their god. Grady made his way among the photovoltaic system. Everything seemed in order until he found a set of cracked panels, five rows deep and in the heart of the array.

He half recalled the hammer of hail two or three days back. It didn’t sound too severe at the time. Although, truth be told, Marty had used the heavy storm as an excuse to cuddle up on the couch, feigning fear, and, well, intimate distractions ensued.

Plus, Grady had a soft spot for ice out of the sky. He grew up in a Midwest without winter snow. Bernie never appreciated it, especially not when shoveling the walkways or trudging hip deep through fresh powder. Still, golf balls dropping out of the clouds never come without consequences.

Tallying the damaged panels, Grady tried not to scowl. He couldn’t blame nature for the occasional inconvenience. He aspired to consider such setbacks part of the compromise of cooperating with life even when it appeared to be working against him. No one’s fault; it simply was what it was.

“‘Don’t get mad at what you can’t control,’” Grady quoted his husband.

Tromping back to the greenhouse, he got on his strip of smart glass. Firing off a text to Regina the weaver, he made sure she didn’t plan on closing up shop early. She replied she’d wait for him. Satisfied, Grady popped in to tell Marty he’d be back in an hour or two.

“Cracked panels?” Marty said.

“Cracked panels,” Grady nodded.

“Probably that hailstorm,” Marty said. “Scared me dontcha know.”

“Yeah, well, you get scared like that again, you let me know.”

“Will do,” Marty said, smirking, as he plucked cherry tomatoes.

“I won’t fix the panels today but tomorrow,” Grady said. “It won’t take too long.”

“No rush,” Marty said. “‘There’s always tomorrow…’”

“‘Because we fixed today,’” Grady finished where his husband trailed off.

“No rush,” Marty said. “‘There’s always tomorrow…’

‘Because we fixed today…’”

He blew a kiss on his way out the door. Hearing Marty quote the influencer poet Elizabeth Escherbach made him think about being sixteen again, when the two met at the 4-H Club learning about perennial crops for soil conservation. Of course, Grady barely learned a thing, too damn distracted by the fem fellow in candy pink gingham. Fortunately, failing to grasp the concept gave him the perfect excuse to ask for help. Their study date turned into a romantic one full of Koi no Yokan implications.

Marty was always quoting Escherbach. She was a voice of their generation, the gentle spur who urged them to reach the tipping point. Her dark chocolate coated cynicism, delicious to devour, infected a whole generation with the rage necessary to fuel real change. Shame she died of Smog Cough before seeing the promised land, though too many young folks passed away from lung disease before the world got wise. Grady’s son certainly did.

****

The jingle of a bell summoned Regina Dickerson out of the backroom. She found Grady Zając shuffling around her weaver’s depot. The metamaterial maker eyed the familiar codger. He struck most folks as perpetually angry, a craggy collection of scowl lines and frown cracks in his leathery visage. Those who knew him recognized the etched evidence of someone glowering at the advancing abyss of pollution spread. It wouldn’t swallow his tomorrow, though it did devour a few pieces of his heart.

“What did you break this time?” Regina asked playfully.

“You oughta know I don’t break things,” Grady said. “I fix ‘em.”

“Then tell me what you’re fixing,” Regina replied. “And how can I help?”

He passed her his smart glass strip. The notepad app contained all the details. While she read them, he idled by a nearby display for silica nanoparticles. The sales screen showed info promising SiO2 NPs-enhanced crop resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses.

“All in all,” Regina said, passing the info over to a tablet, “it doesn’t look so bad. I got most of what you need ready to go.”

“Well, alright, alright,” Grady nodded in approval, sauntering back to the counter.

“That is unless you’re ready to upgrade,” she said, glancing at him sidewise.

Grady harrumphed.

“Not trying to upsell you,” Regina said, setting the tablet aside. She gestured at a display at the far end of the depot saying, “You’re still using the last gen of solar panels. These new ones are bio-inspired.”

“And I’m sure they’re wonderful,” Grady said.

“They sure are,” Regina replied, leaning on the counter between them. “Based on a butterfly wing, we got hydrogenated amorphous silicon, thin sheets forming all kinds of tiny holes. They catch light like nobody’s business.”

“Uh huh.”

“Then there’s them.” She pointed to another display. “I’m weaving the metamaterials for a replacement that involves those.”

“And they are?” Grady said, overtly glancing at a wall clock.

“Femtosecond-laser-treated tungsten surfaces,” Regina said, then added with a sparkle in her voice, “I’m weaving up some nanocomposite materials for quantum dot solar concentrators to go with it.”

“Let me ask you a question,” Grady said. “Do folks buy whatever the hell it is you’re talking about just to pretend as if they know what you just said?”

“Maybe,” Regina smirked. “But all in all, I’m talking about improved nanotechnology, microscopic crystalline structures that’ll bump the efficiency of your energy harvesting from forty to sixty-six percent guaranteed.”

“Look,” Grady folded his arms across his chest. “My setup is not obsolete.”

“Not yet,” Regina jumped ahead of his predictable penny-pinching decline. “But it will be eventually, and it doesn’t hurt that the government pays for upgrades now.”

“I know all about the tax credits,” Grady said.

“Not just a credit no more,” Regina said. “They pay for the whole thing now. When it’s an upgrade.”

Grady cocked an eyebrow. Regina suppressed a smile. The grumpy codger shuddered. In essence, shaking off the idea.

“Nah,” Grady said. “I’m happy with the hybrid. It gets the job done.”

“Fair enough,” Regina said. The slightest tick of a smirk went up, knowing she planted the seed. Maybe not today but soon, she suspected the offer would lure him back. Meanwhile, Regina tapped at her tablet, sending orders to the stock runners in the rear warehouse to assemble Grady’s order. Making small talk she softly remarked, “Speaking of folks behind the times.”

Grady rolled his eyes. Although he said nothing, the ensuing silence inspired him to gesture for Regina to continue.

“You hear about Zeke Fogel?” she asked.

“No, what about him?”

“He got arrested for shooting at a sky scrubber.”

“Sonuvabitch,” Grady said. “Damn kid takes after his old man too much.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” Regina said.

The Fogel family perceived progress as a spark to ignite all kinds of paranoia. She knew Grady used to have to endure the daddy’s rants whenever he picked up his grandson. He’d often come into her shop to buy something, then vent about an unpleasant exchange with Papa Fogel. That is until the two young men got to high school.

Regina had heard rumors of a falling out, but since Bernie never wanted to talk about it, and Grady never pressed him for details, she remained in the dark. Suffice it to say, Zeke’s daddy instilled in his son a deep mistrust of atmosphere cleaners. As if those zeppelin-inspired drones were some kind of silent assassins floating quietly along, mind control chemical dumping dirigibles, or whatever crackpot conspiracy theory sprang in his brain.

“It’s just up there,” Regina said. “Sucking whatever bad shit is in the air. Zeke gets it into his head that the thing gets low enough, he gonna shoot it down. Cops arrested him for blasting homemade pipe bombs out of a potato gun.”

“Poor guy must be off his meds again,” Grady said.

“No doubt,” Regina said. “You ever get the feeling we started focusing on the world so ‘s we could stop thinking about the people in it?”

“Maybe,” Grady sighed. “One’s easier to fix than the other, I tell ya what.”

****

Pulling up in front of the house, Grady noticed music spilling out the windows. He wondered what put Marty in a festive mood. Plugging in the pickup, he cracked his neck. Grady felt the weight of the day pressing down on him. He hoped a cup of coffee might be enough to keep pace with his apparently perky husband.

Two tattered bags resided on the floor by the front door. The mismatched pair didn’t strike Grady as fancy enough to belong to his Uncle Tim and Aunt Bruce. Laughter lured him towards the kitchen. He struggled to figure any other guests who’d be as unexpected yet clearly welcome.

Marty sat at the kitchen table sipping a mug of tea. He positively glowed. It made Grady smile. Stepping into the kitchen, he saw a young man in flannel and denim seated across from Marty. He looked familiar, but Grady’s brain couldn’t call to mind any names.

Seeing him coming, Marty sprang up. He practically hopped around the table to grab his husband. Holding Grady’s arm, he presented their young guest.

“Hon,” Marty said. “Bernie is back.”

Whatever pleasantness Grady may’ve been prepared to present quickly melted off his face. He glowered at his grandson. The kid stood, rising up a bit over six feet tall. Grady had to tilt his head back to keep glaring at Bernie.

“What do you want?” Grady grumbled. “Ya need money?”

“No, sir,” Bernie said.

“You running from,” Grady shrugged, “whatever?”

“Nope,” Bernie shook his head.

“He’s come home,” Marty said softly. “Ain’t that grand?”

Grady snorted. Marty, understanding its meaning, patted his husband on the shoulder. Slipping away, he gestured for Bernie to sit back down again. The two took their seats at the table.

Grady turned around.

“Where you goin’, shug?” Marty called after him.

“I gotta put those new solar panel parts in the workshop,” Grady hollered back. “Don’t want them sitting outside in case of something foul.”

“You need a hand?” Bernie asked.

“No.”

The front door slammed shut. Grady stormed over to the pickup. Grumbling and growling, he started unloading the replacement parts for the solar panels. By the time he finished, he was a sweaty simmering rage.

“Maybe I did need a hand,” he muttered.

If he wasn’t so tired, saying as much might’ve made him madder. Fuming, he started back towards the house. Coming in quietly, he heard soft chatter from the kitchen. Grady went straight upstairs, into the shower to cool down, and then off to bed. He pretended to be asleep hours later when Marty climbed in beside him.

“Don’t ruin this,” Marty said after a brief silence.

“I didn’t break anything,” Grady said.

“Aren’t you the one who fixes things?”

Grady replied by saying nothing as he shifted onto his side. Marty responded to the implicative action by doing the same. For a while they lay with their backs to one another, but eventually, Grady left the bed for the couch downstairs.

****

He awoke the next day feeling stiff. Rising, Grady’s bones crackled as muscles groaned in a way that suggested he may’ve gotten too old for sleeping on the sofa. Squinting in the daylight, the living room seemed too bright for early morning. It slowly dawned on him he’d left his smart glass upstairs when he hurried away angry. He was nowhere near the synthetic rooster crow that roused him most of his life.

Staggering into the kitchen he found cold coffee in a pot. Slurping it down in his favorite drinkware, a ceramic brown mug with crudely painted birds in turquoise paint, Grady fetched clothes from the bedroom. Half awake, he still knew well enough to creep like a ninja avoiding his husband. Yet the house appeared empty.

Passing his grandson’s bedroom on the way back downstairs, he noticed the bed sheets appeared a bit rumpled. The record by Carnival of Animals was back on the shelf. Bernie had clearly slept there. His bags were on the floor as well, though they didn’t appear to be unpacked.

Grady went downstairs then outside. He may have lost the morning, but he remained determined to get the solar panels replaced before the evening. He went straight into the workshop. There he found zero indication of anything he needed. Neither tools nor replacement pieces, although his search revealed that the flat deck 8-wheeler wagon was also awol. The cold coffee finally kicked his sleep-addled brain into gear.

He went for a walk. Long before he reached the solar array, he saw Bernie fumbling about.

“You even know what you’re doing?” Grady asked when he got closer.

“I remember what needs to be done,” his grandson replied. “We did this once or twice, ya know?”

“Ain’t like riding a bike,” Grady said.

“Then it’s a good thing I installed them in Arizona.”

“So.” Grady shuffled his feet. “That’s where you been?”

“Among other stops,” Bernie replied. “It’s a big world out there.”

“And you just had to go see it,” Grady said.

He felt the invisible hand of his husband smacking the back of his head. Marty would not care for him stoking old fires, especially not ones that could turn into uncontrollable blazes. Grady braced for Bernie’s retort.

Instead of saying anything, he remained silent. He finished with the solar panel and put the tools away. He flickered a glance at his grandfather, then pretended to be observing some connections closely.

“That the mug my dad made?”

“Hm?” Grady cocked an eyebrow. He looked at one of the painted birds and added, “Yeah, it is. He’s still where we planted him, if you wanna visit while you’re here.”

“I didn’t expect him to be gone,” Bernie said.

“No, I s’pose not.” Grady turned to walk away.

He heard the groan of wheels in need of oil as Bernie started pushing the flat deck wagon back to the workshop. The two walked along in silence. The only sound between them was the metal clank and rattle of the wagon bouncing off every bump in the road. Grady used to have the boy sit on the flat deck after chores, and they’d treat it like a ride. He remembered the kid laughing so happily.

They marched into the workshop silently. Bernie steered the wagon, parking it in the usual spot. Grady fired up the swarm app on his smart glass. Checking the A.I. regulator’s report, he slurped the last of his cold java.

“Don’t suppose you made a fresh pot,” Bernie said.

“Didn’t need any fresh,” Grady said. “There was enough left for a cup.”

“How come you never make fresh pots?” Bernie smirked.

“Hey,” Grady said. “There’s nothing stopping you from making fresh pots.”

Then he frowned.

“Bad report?”

“More annoying than bad,” Grady replied.

He started searching around the workshop.

“Insects?” Bernie said more than asked.

“Yep.”

“Ya know,” Bernie said. “If you had a smart irrigation system with pipes through the field, you could just store some pesticide in a tank. The A.I. would handle the rest.”

“I could,” Grady said rifling about for canisters of eco-friendly pesticide. “But then I’d still need drones for fertilizer. Plus, pipes don’t harvest. They sure as shit don’t see bugs.”

He found the empty canisters of organic pesticide easily enough. The full ones should have been nearby. The old man muttered a curse. He couldn’t believe how sloppy he was getting.

“Need a hand?” Bernie asked.

Grady hesitated. Making noises implying negative, he told the boy to gather some pheromone traps from a crate across the workshop. Meanwhile, Grady finally rustled up some canisters of enviro-friendly insecticide. Outside, he called in drones.

The A.I. regulator sent watering drones to deposit their remaining liquid in the farm’s rain tower. Four of them soon landed near Grady.

“You still using that old stuff?” Bernie asked.

“It still works,” Grady replied. “Better than what folks used to use.”

“Poisoning themselves along with the bugs.”

“Boy howdy,” Grady said. “You make it sound like you were listening.”

“When I was in Chicago,” Bernie said, setting traps on the ground, “I spent some time with a person. She said the future is these fungal pathogens. Microbial control agents she called them.”

“Hmmm,” Grady said, attaching a canister to a drone. “It’s never just one simple cure.”

“I hear ya. Grandpa Marty was telling me the Jensens down the way got their field full of bugs that eat the bad bugs.”

“Since when are you so interested in such things?”

Bernie thrust his hands deep in pockets. He looked off towards the road into town.

“Just making conversation,” he said.

Grady replied with a gravelly sigh. He finished topping off the drones. Tap-tap on the app, and they were into the sky. Wasn’t long before the A.I. had them misting murder on the unwelcome pests. Bernie kicked a clump of dirt.

“I like the stuff your Grandpa Marty uses,” Grady said. “He mixes a killer cocktail out of neem oils, and gly-something-erol monooleates, and ethyl-what’s-its. Hell if I know what else.”

“But it works?”

“Works in the greenhouse well enough,” Grady said. “Sometimes I think about getting it in bulk, seeing if it works all over.”

“But it’s expensive?” Bernie guessed.

“Yep,” Grady glanced at him sidewise. “This Chicago person. You together long—stay there long?”

“Year or two,” Bernie said. Seeing his grandad tense he added quickly, “Air ain’t like it was when my Pops went there for college. I mean, you can swim in the Great Lakes again.”

“Air ain’t like it was when my Pops went there for college. I mean, you can swim in the Great Lakes again.”

“Good to know,” Grady nodded, his face tight.

It did feel like they had crossed the tipping point. At least things seemed to be moving in the right direction. The needle retreating from red—his son, Thad, always believed it was possible. He didn’t just head off to college to learn better agricultural techniques for the farm. He wanted to figure out new ways to improve everything. Eight years aiming at a high degree, he came home from Chicago with a baby and a bad set of lungs. He said the boy’s momma died of lead poisoning. That was supposed to be the end of city life for the Zając clan, if Grady had anything to say about it. And he said it a lot.

“Do me a favor,” Grady said, watching the swarm disperse death. “Go make a fresh pot.”

“Yes, sir.”

He handed Bernie his mug as his grandson passed. Then Grady watched him walk towards the house. It felt like a scene that should have been but never was.

He gathered up the pheromone traps. Carrying the armload to the greenhouse, as expected, he found Marty inside tending to crops.

“Can I help you?” Marty asked.

“Swarm saw bugs,” Grady replied. “I brought you traps in case they start creeping in here.”

He set them on a nearby table. Marty didn’t say anything. Grady nodded. On the way out, he cast a remark over his shoulder.

“It’s nice to know he’s okay,” Grady said.

“Yeah, it is.”

****

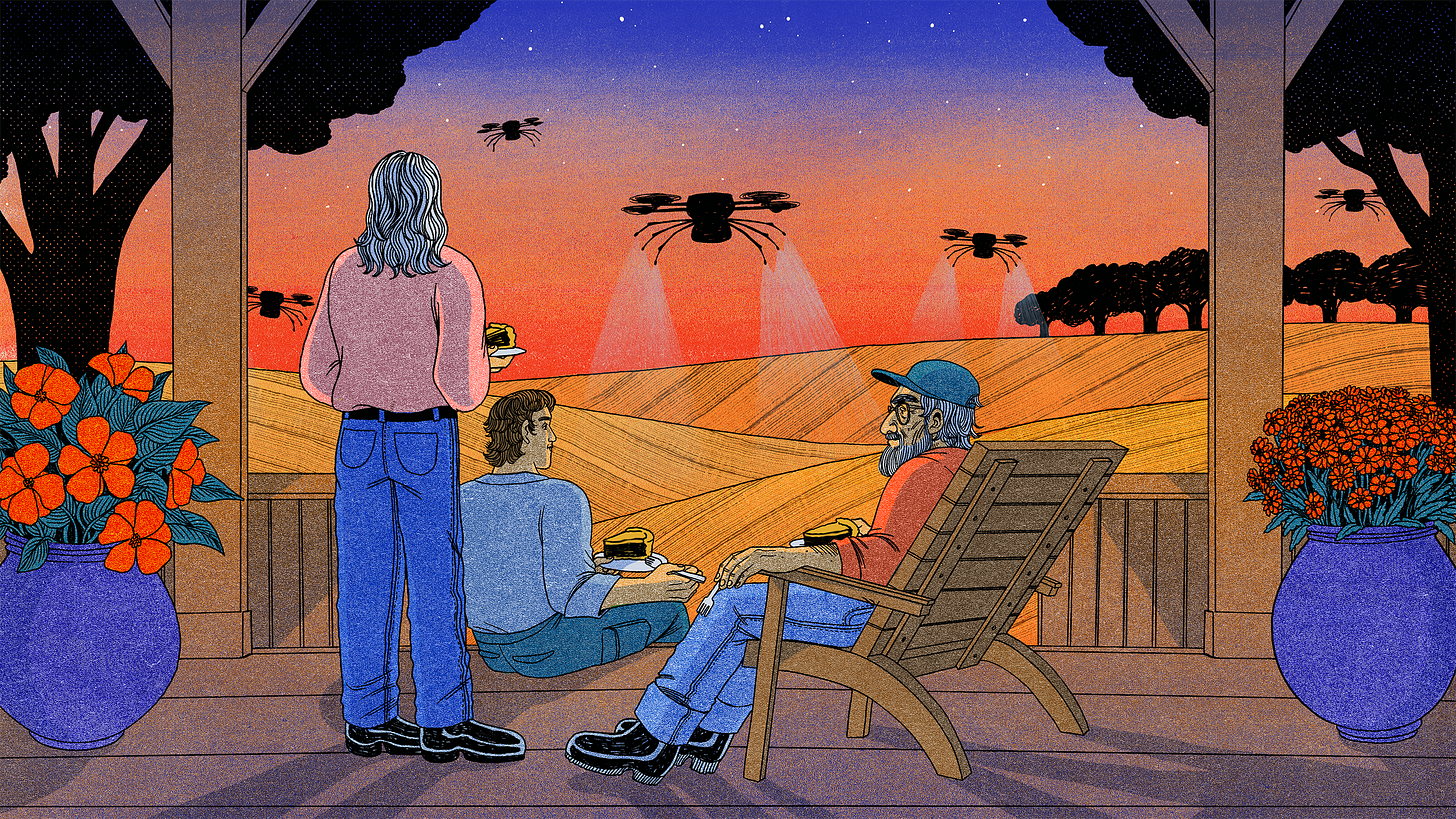

Crickets chirped in the growing darkness. Grady sat on the porch sipping cold lemonade. The blinking swarm continued to mind the field. Its flickering lights seemed to be joining the bevy of blinking fireflies.

Footsteps sounded from inside the house, someone approaching the front door. Bernie stepped out. He took up his old seat on the porch steps.

“Bet there’s nothing like this in Chicago,” Grady said.

“Nope,” Bernie said. “Nothing like it in any city I been.”

The two sat in silence for a minute.

“Ya know,” Bernie said. “The world isn’t the filthy place you made it seem.”

“Not anymore,” Grady said. “It took a lot of work.”

“Yeah, but you weren’t the only one working.”

“Never said I was,” the old farmer grumbled. “I only ever said if people take care of their own little slice of the world, it all adds up.”

His grandson nodded.

“I’m just saying there’s plenty of ways to improve the world.”

“And I think it’s best I stick to what I’m good at doing,” Grady said.

“Funny you should say that,” Bernie said. “That’s kinda why I came back.”

“I’m just saying there’s plenty of ways to improve the world.”

“And I think it’s best I stick to what I’m good at doing,” Grady said.

“Funny you should say that,” Bernie said. “That’s kinda why I came back.”

The two exchanged glances. Grady nodded. Bernie smiled. His granddad grinned back.

Marty popped out to ask if anyone wanted pie. No one could say no. He enlisted Bernie as assistant. The pair soon returned with slices on plates. The three sat munching on the porch. Rolling back and forth in a rocking chair, Grady felt a certain peace he hadn’t known for years.

He started to chuckle. Marty looked at him with a bemused expression.

“‘This carnival of animals,’” Grady sang. “‘The lost and the damned.’”

“‘Racing for ruin,” Bernie sang. “‘I do not understand.’”

“‘How these lunatics delight in the end at hand,’” the pair sang together. “‘The obvious demise of poisoned land.’”

“Is this from that noise you two maniacs used to listen to?” Marty asked.

“Boy,” Grady said gruffly. “Bring the noise.”

“Yes, sir,” Bernie smirked.

He hurried off upstairs to fetch the record.

“And you,” Grady pointed at his husband. “Go on, beautiful, get the white lighting.”

“Oh,” Marty cocked his head to one side. “We celebrating something?”

“We’re celebrating today,” Grady said.

Marty smiled. He knew what his lover meant.

“‘What point is there to tomorrow, if we can’t celebrate today?’” Marty quoted Escherbach.

“‘Because tomorrow is coming,’” Grady said. “‘If we repair the way.’”

Stay tuned…

Thanks for tuning in to 12 days of climate fiction! Make sure you’re subscribed to get weekly updates, stories, interviews, behind-the-scenes, and more of Tractor Beam, right here on Substack and in your inbox.

Know someone who is an avid sci-fi reader, passionate about climate work, or loves to get their hands dirty in the soil? Spread the word and share our newsletter. And give us a follow on Bluesky and Instagram to stay connected on the latest. Let’s grow a better future together.